Milwaukee, Wisconsin

Cincinnati, Ohio

With the recent release of the 2023 National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) document “Managing Hazardous Drug Exposures: Information for Healthcare Settings,”1 and the impending implementation of USP Chapter <800>2 on November 1, 2023, renewed interest has been generated in performing an Assessment of Risk for inpatient healthcare workers who may have contact with hazardous drugs (eg, chemotherapy, antineoplastic drugs). As necessary as that effort is to ensure worker safety, it’s now time to take a hard look at performing an assessment of risk for chemotherapy delivered at home—whether it be injectable, topical or oral. An assessment of risk determines who may be at risk from exposure to the drugs and the factors that may put someone at risk.

An example of the rapid increase in home delivery of chemotherapy is the experience of the Penn Center for Cancer Care Innovation led by Justin E. Bekelman, MD, in Philadelphia. Already in operation at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Penn Center scaled up from 39 patients in March 2020 to 310 patients by the end of April of that year.3 Although this exponential growth may not be typical, it’s an example of the feasibility of providing sophisticated treatments in the home care setting. Such provision requires expanding the NIOSH Assessment of Risk concepts to accommodate both patients and family members.

If we consider the Table of Control Approaches provided in the 2023 NIOSH document, we can modify it to accommodate delivery in the home. Let’s consider first the formulations involved. They may include oral dosage forms, such as tablets and capsules, oral liquids, topical drugs, and IVs. With respect to delivery mechanisms, closed system drug-transfer devices for home IV infusion should be a standard of practice. The primary line of defense for home care involves personal protective equipment (PPE) and spill kits. But perhaps the most important risk mitigation is providing information to the patient, caregivers, and family members on the importance of being prepared and knowing what to do in each instance of potential exposure.

Identifying People at Risk

In the home health environment, we also must consider who needs protection. Obviously, the home health nurse should have hazardous drug training and be provided with the necessary PPE as well as an appropriate spill kit, chemotherapy sharps container, and hazardous waste container for any unused drug should the treatment be discontinued. According to an article4 by Eisenberg and Klein, not all home care nurses have received the necessary training, given the rapid explosion in home care IV therapy, driven in part by the COVID pandemic, as noted above.

The second group of people who need education and/or protection are the family members of the patient, which may include infants, children, pregnant and elderly family members, and pets. This is especially important when a family member is also the primary caregiver.

Finally, patients need the equipment and knowledge to ensure their treatment remains as confined as possible, based on their ability to manage their own care.

Hazardous Drugs in the Home

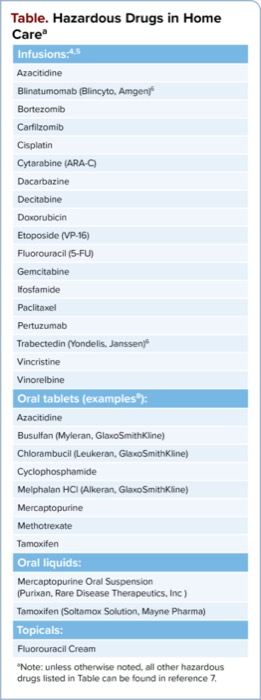

A good starting point is to identify those drugs that may be administered in the home, typically by the IV, oral, or topical route. The Table provides a list of common hazardous IV, oral, and topical drugs administered in the home.5 Although each of these dosage forms is associated with different inherent risks, there are some areas of common concern.

| Table. Hazardous Drugs in Home Carea |

| Infusions:4,5 |

|---|

| Azacitidine |

| Blinatumomab (Blincyto, Amgen)6 |

| Bortezomib |

| Carfilzomib |

| Cisplatin |

| Cytarabine (ARA-C) |

| Dacarbazine |

| Decitabine |

| Doxorubicin |

| Etoposide (VP-16) |

| Fluorouracil (5-FU) |

| Gemcitabine |

| Ifosfamide |

| Paclitaxel |

| Pertuzumab |

| Trabectedin (Yondelis, Janssen)6 |

| Vincristine |

| Vinorelbine |

| Oral tablets (examples8): |

| Azacitidine |

| Busulfan (Myleran, GlaxoSmithKline) |

| Chlorambucil (Leukeran, GlaxoSmithKline) |

| Cyclophosphamide |

| Melphalan HCl (Alkeran, GlaxoSmithKline) |

| Mercaptopurine |

| Methotrexate |

| Tamoxifen |

| Oral liquids: |

| Mercaptopurine Oral Suspension (Purixan, Rare Disease Therapeutics, Inc ) |

| Tamoxifen (Soltamox Solution, Mayne Pharma) |

| Topicals: |

| Fluorouracil Cream |

a Note: unless otherwise noted, all other hazardous drugs listed in Table can be found in reference 7. |

Awareness of Exposures

It’s extremely important for all healthcare professionals involved in prescribing, administering, or overseeing home care to emphasize the added dangers posed by hazardous drugs to the patient’s family members and other caregivers. Although there is a general understanding that it is not safe to ingest someone else’s medication, many people are not aware that simply touching tablets or creams or being exposed to the toilet effluent of someone receiving chemotherapy may be detrimental. Preparing an Assessment of Risk for all hazardous drugs potentially dispensed for home use and developing an operational strategy to minimize the risk, along with appropriate patient information, can protect healthcare professionals providing home care. These measures also can protect relatives, caregivers, including children living in the household, and the patient. This assessment can take the form used in other industries, such as when assessing living conditions for elderly individuals or evaluating general safety hazards.

Assessing the Risk

Similar to an assessment of risk performed in a healthcare setting, in the home setting, the form of exposure is the primary consideration followed by the route of administration. Patients receiving IV chemotherapy infusions provided either by a home healthcare professional or through a pump have an increased risk due to the spill and splash potential, as are their families. Creams and liquids provide the next concern, with tablets and capsules being at the other end of the spectrum, unless they must be cut, crushed or divided.

Patients who are incapacitated in any way due to illness pose a second level of risk, particularly if they are very young. The side effects of chemotherapy, including nausea, vomiting, and/or diarrhea, can also increase the risk of exposure in caregivers, who must be prepared to manage these situations without endangering themselves.

Finally, lifestyle risks including falls, management of injuries involving blood and other body fluids, and sexual activity should be actively discussed. Several excellent websites are available to explore these aspects in detail.

Risks to Healthcare Professionals

Although there is a relatively intense focus on the training of inpatient oncology pharmacy personnel, nurses, and related professionals who may be exposed to hazardous drugs, ensuring that home care nurses and related personnel receive appropriate education is more challenging. Not only must the healthcare professional delivering chemotherapy in the home be fully prepared to protect themselves during IV infusion, but they also should be trained to provide patient and family education that results in minimal exposure to the drugs.

With respect to PPE, the administering nurse should be prepared to don 2 pairs of chemotherapy gloves, an appropriate chemotherapy gown, and eye and face protection. The same risk of spills, nausea and vomiting, IV failure, and similar incidents that occur in healthcare settings actually are exacerbated in the relatively uncontrolled home setting. Two pairs of chemotherapy gloves also should be worn when applying creams and administering oral medication. These behaviors also set an example for family members and caregivers who may be assisting the patient. If tablets must be crushed, such as when being mixed with food, the person preparing the drug should use respiratory protection.

With respect to disposal of needles, IV sets, and other paraphernalia, a yellow trace chemotherapy waste container should be provided by the home care organization and the materials brought back to the organization for proper disposal, ideally by incineration. A small black container labeled as Hazardous Waste Pharmaceuticals also should be available in case the infusion must be stopped prior to completion. The unused IV contents and the IV bag should be placed in the black container, the container sealed and returned to the infusion pharmacy for disposal as hazardous pharmaceutical waste.

Patient Risks and Responsibilities

The primary goal of treatment in the home is to ensure that the patient receives the correct dosage of medication at the correct time. To achieve this, many patients use a plastic “pill container” that is labeled with the days of the week and contains compartments up to 3 or 4 times per day. Although this compliance strategy is appropriate for non-chemotherapy drugs, it should not be used for oral chemotherapy. Chemotherapy should be stored in the original container, away from children and pets, and inside a separate container or sealed bag if stored in the refrigerator. The outer container should be clearly labeled as chemotherapy or hazardous drugs, and all family members should be instructed not to touch it unless they are the primary caregiver, in which case they should receive additional safe handling instructions.

If self-administering, the patient should wash their hands for 20 seconds before and after touching their medication to minimize exposure to family members. Patients should be advised not to cut or crush tablets or open any capsules unless instructed to do so. If medication gets on skin, the area should be washed with soap and water. If any redness, pain, or burning occurs, the healthcare provider should be called. If medication gets into the eyes of the patient, the eyes must be flushed with water for 10 to 15 minutes with the eyes open, and the healthcare provider contacted immediately.

Personal Hygiene

Patients need to understand that all their bodily fluids will contain chemotherapy during the course of therapy. For IV infusions, traditionally a period of 48 hours to 5 days after completion and 7 days after oral treatment are considered appropriate. Patients should be encouraged to use a separate toilet, if possible, to sit on the toilet to avoid splashing or contamination, to close the lid when flushing, and to flush twice after each use.

Since all bodily fluids may contain chemotherapy, patients should be judicious with personal contact, because saliva and sweat may be contaminated. With respect to sexual activity, risks to both the patient and the partner should be considered. St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital provides an excellent summary of safe sex recommendations during treatment,9 which includes the following:

- The patient should have a blood platelet count of at least 50,000 to protect against bleeding and bruising during sex and an absolute neutrophil count of 1,000 or higher to enable the body to fight yeast or urinary tract infections.

- If any radioactive therapy is involved, the patient should not have sex until the material is removed.

- A condom or other form of barrier protection should be used to protect against sexually transmitted infections due to a weakened immune system during chemotherapy.

- An unplanned pregnancy during cancer treatment poses a risk to the developing child, so birth control should be encouraged.

Caregiver Risks and Responsibilities

It’s important for the caregiver to be properly informed about the proper storage and administration of the chemotherapy. It should be prepared and given to the patient in an area away from all food and preferably in a manner that makes it inaccessible to small children at all times, such as a high counter. The caregiver should wear at least 1 pair of disposable chemotherapy gloves and pour the tablets or capsules into a cup and not their hand. They also may be advised to wear respiratory protection and/or glasses, especially if it is likely the patient may choke or experience nausea and vomiting.

Caregivers should wear disposable respiratory protection such as N95 masks if there is a chance of inhaling the chemotherapy, such as when needing to crush or split tablets. Although tablets may be split using a tablet cutter available at pharmacies, patients should be advised to speak with their pharmacist before manipulating them. If at all possible, it is preferable to dispense the appropriate size dosage form. If manipulation is necessary, it should be done on a surface inaccessible to children, such as a high counter, covered with disposable plastic, and performed away from ceiling or table fans or vents. After giving the dose, the caregiver should be instructed to wash their hands for 20 seconds in warm, soapy water and to clean the preparation area when finished.

Caregivers should be instructed to exercise similar personal hygiene precautions as the patient for at least 48 hours if they need to clean up any bodily fluids, including vomit, blood, urine, or bowel movements. Having a cleanup kit for these activities should be encouraged, and should include gloves and protective clothing, such as a chemotherapy gown, a face shield or goggles, disposable towels and wipes, and larger plastic bags for double bagging of cleanup materials. If medication contaminates clothing, the clothing should be handled with gloves, kept away from bodily contact with the patient and the caregiver, and washed twice separately in hot water.

Chemotherapy Spills and Leaks

Infusions should be delivered in an area that is easy to clean, avoiding upholstered furniture and carpeting, if possible. If a leak occurs while a healthcare professional is on-site, they should follow a standard protocol for spill cleanup, optimally by using a spill kit provided by the infusion pharmacy. If a healthcare provider is not present, the patient or caregiver should don 2 pairs of chemotherapy gloves, wrap paper towels or other disposable material around the connection, clamp the tubing, and call their healthcare provider immediately. If a patient is using a pump, they should be instructed on how to turn it off and return to their provider for assistance.

Disposal of Hazardous Drugs

If oral chemotherapy needs to be discarded from the home, it should be kept in the original container, placed in a closed Ziploc® bag, and, if possible, taken to a pharmacy or other location that maintains a medication disposal kiosk. Some pharmacies also offer individual mail-back programs for consumers. If an IV infusion must be discontinued, the attending home care nurse should have a black hazardous waste pharmaceutical container available, which should be sealed and returned to the provider pharmacy. If a portable IV pump fails or must be discontinued, the patient should return to the clinic for removal and disposal of the pump and contents.

Home Spill Kits

Ideally, the infusion pharmacy should provide a spill kit for the patient with instructions for use. If not, the patient should be instructed to assemble their own spill kit, including 2 pairs of disposable chemotherapy gloves, paper towels or other absorbent, disposable material, dish soap or laundry detergent, and 2 sealable plastic bags of a 1-gallon size or larger.10 The kit should be readily available during infusion or while the patient is wearing a portable pump.

Risks to Bystanders

Very little study has been done regarding the level of exposure to hazardous drugs in the home for family members and other “bystanders.”11 Given the widespread surface contamination documented in controlled healthcare settings, it would be reasonable to assume a fairly substantial exposure risk, at least during the most active chemotherapy infusion time frames.

Family members and caregivers may be exposed through absorption, inhalation, or ingestion. Anyone handling IV bags, tubing, infusion pumps, or oral medications should wear 2 pairs of chemotherapy gloves and carefully double-bag all waste prior to disposal. A separate drug administration area should be set up away from any area where family members are eating or drinking. If family members are involved in injecting hazardous drugs, they must be trained in proper administration and sharps safety. A sharps container must be available and instructions provided as to where to dispose of the device. Some states, such as Wisconsin,12 prohibit the disposal of sharps containers in municipal trash.

Pet Care and Concerns

With respect to a risk to animals in the household during chemotherapy use, it would be wise to limit licking of the skin of the patient during and after chemotherapy. It’s also important to keep pets away during infusions. Cases have been reported of pets chewing through chemotherapy lines or through a bag with all the negative consequences. Keeping the lid of the toilet closed to pets also is important to avoid them ingesting any residue of chemotherapy. With the rapid rise of chemotherapy treatment of pets, the same precautions apply, but for the opposite reason. Management of pets receiving chemotherapy poses similar but additional risks, but that’s another story!

Peer reviewers: Brett Benfield, PharmD, MS, the director of Home Infusion and Compounding, Fairview Health Services, and Holly Mahowald, BSN, OCN, PHN, CRNI, the FHI nursing supervisor, Fairview Home Infusion.

Dr. Connor reported that he is a member of the advisory board for Splashblocker, LLC. The remaining sources reported no relevant financial relationships.

References

- National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In: Hodson L, Ovesen J, Couch J, et al. Managing Hazardous Drug Exposures: Information for Healthcare Settings. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, NIOSH; April 2023. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2023-130. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://doi.org/10.26616/NIOSHPUB2023130

- USP. USP chapter <800> hazardous drugs—handling in healthcare settings. In: USP 31–NF 26. Published February 1, 2016. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.usp.org/compounding/general-chapter-hazardous- drugs-handling-healthcare

- Bekelman JE. Home infusions and home-based chemo: the innovation of Penn Cancer Care at Home. Penn Medicine Physician Blog. Published June 15, 2020. Accessed June 21, 2023. www.pennmedicine.org/updates/blogs/ penn-physician-blog/2020/june/infusion-therapy-and-home-based-chemo-the-innovation-of-penn-cancer-care-at-home

- Eisenberg S, Klein C. Safe handling of hazardous drugs in home infusion. J Infus Nurs. 2021;44(3):137-146. doi:10.1097/NAN.0000000000000424

- Information provided by Brett Benfield, PharmD, MS, the director of Home Infusion and Compounding, and Holly Mahowald, BSN, OCN, PHN, CRNI, FHI nursing supervisor, Fairview Home Infusion Services. (Email communication June 20, 2023).

- Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH list of hazardous drugs in healthcare settings 2020. Published June 19, 2020. Accessed June 26, 2023. www.cdc.gov/niosh/docket/review/docket233c/pdfs/ DRAFT-NIOSH-Hazardous-Drugs-List-2020.pdf

- Department Of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. NIOSH list of hazardous drugs in healthcare settings 2016. Published September 2016. Accessed June 26, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ docs/ 2016-161/ default.html

- Excreta. Eisenberg S. Published 2019-2023. Accessed June 26, 2023. www.setheisenberg.net/hd-excreta

- St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Sexual health during cancer treatment. Reviewed: July 2022. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://together.stjude.org/en-us/patient-education-resources/support-daily-living/sex-and-treatment.html

- Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Safe handling of chemotherapy and biotherapy at home. Updated Dec. 12, 2022. Accessed June 21, 2023. www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/patient-education/safe-handling-chemo-bio

- Polovich M, Olsen M, eds. Safe Handling of Hazardous Drugs. 3rd ed. Oncology Nursing Society; 2018:77.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Managing household medical sharps. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://dnr.wisconsin.gov/topic/HealthWaste/ HouseholdSharps.html