Health systems continue to make significant inroads into the specialty pharmacy market, with more than two-thirds of multihospital systems launching programs in a recent five-year period. But despite those gains, the sector still faces major roadblocks, including a lack of access to limited distribution drugs (LDDs) and payor contracts, according to ASHP’s inaugural National Survey of Health-System Specialty Pharmacy Practice.

Still, many health systems have succeeded in overcoming those challenges, in part by leveraging the superior continuum of care they claim is a hallmark of their practice model. Whether it’s streamlining the prior authorization (PA) process, reaching for legal tools to break down payor walls, or speeding the pharmacy and therapeutics (P&T) specialty drug approval process, health systems have shown they are up to the challenge, as outlined in several presentations at the 2021 virtual ASHP Specialty Pharmacy Conference.

The conference kicked off with a presentation of the new survey, with several of the findings underscoring key practice issues and frustrations for health-system specialty pharmacies (HssPs). The survey was sent to 230 contacts at 206 different HssPs; 114 (53%) completed the survey. The survey included 99 questions over eight domains addressing demographics, workforce issues, operations and payor access, among others.

Most HssPs dispense fewer than 45,000 specialty prescriptions per year and have an annual gross revenue of less than $100 million, the survey found. Most of these specialty pharmacies are relatively new, with 73.8% of survey respondents saying their organization has offered specialty pharmacy services for six years or less.

“We also learned from this survey that HssPs are primarily regional in their approach,” said Craig Pedersen, PhD, RPh, the pharmacy manager at Virginia Mason Medical Center, in Washington state, who conducted survey development and analysis. “The majority have five state licenses or fewer; slightly over one-third only have one, although some have many—even up to 50 if they want to serve all 50 states. But most are like my health system: We are located in Washington and have licensees in Alaska, Arizona, California and Oregon. But we’re not reaching into the Midwest or the East because those aren’t patients our medical center serves.”

Some of the survey’s other takeaways:

Integration. The HssP practice model is integrated into specialty clinics, with 64.9% of respondents reporting that they have HssP pharmacists dedicated to specific clinics and involved in treatment decisions and drug therapy selection before prescriptions are written. “This finding is consistent across specialty pharmacies regardless of size,” said JoAnn Stubbings, BSPharm, the former associate director of specialty pharmacy at the University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy, who served on the advisory committee for the development of the survey. “This upstream involvement of HssPs allows for appropriate drug selection before PA is submitted, as well as management of safety parameters, leading to faster medication access and better patient outcomes.”

Pharmacy versus medical benefit. The HssP business model is focused on self-administered (96.2%) and clinic-administered medications (80.2%) under the pharmacy benefit. Only a small number of HssPs provide self-administered (31.1%) or clinic-administered medications (22.6%) under the medical benefit. “What I’ve seen in most health systems is that the medical benefit is typically managed by another area of the pharmacy enterprise, but that is changing,” said Ms. Stubbings, a member of the Pharmacy Practice News editorial advisory board. “There is significant overlap, and we are starting to see HssPs building infusion suites and enter home infusion, and this is becoming increasingly important. We hope to identify these trends in a future survey.”

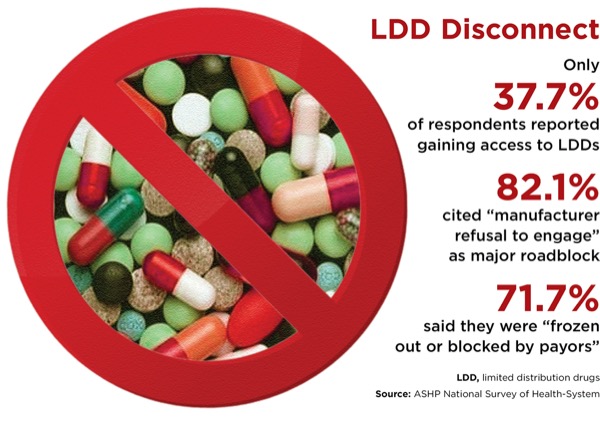

Access still a challenge. HssPs have had only moderate success in gaining access to LDDs, with resistance from manufacturers and payors cited as major roadblocks (Figure).

Inflammatory conditions No. 1. The most common therapeutic categories served were inflammatory conditions and hematology/oncology (both 92.4%), hepatology/hepatitis C (85.7%), neurology/multiple sclerosis (78.1%) and infectious disease/HIV (70.5%). More than half of all respondents indicated that their HssPs also provided care in cardiology, endocrinology, cystic fibrosis, respiratory/pulmonary arterial hypertension and solid-organ transplant, and 90% said they offer PA support.

340B, shrinking reimbursements among other challenges. HssPs see access to payor networks (82.9%), 340B Drug Pricing Program changes (42.9%) and shrinking reimbursement from payors (40%) as their top challenges, with new populations to serve and new therapeutic categories rated as leading opportunities for growth.

“HssPs are responding to these challenges by exploring new payment methods, new models such as value-based care, and further integration of services,” Ms. Stubbings said. “Overall, I am optimistic about [trends] that could positively impact our model. Some are legislative, some market-based, some based on our advocacy. Provider status is one change that is getting closer at the state and federal level, and could offer new opportunities for clinic-based pharmacists to be recognized and bill for their services. Some states are banning white bagging, and we are also seeing legislation proposed at federal level on DIR [direct and indirect remuneration] reform.”

Legal Tools Help Protect Specialty Pharmacies

HssPs have some legal tools they can use to address network access and other practice challenges cited in the ASHP survey, Jesse Dresser, Esq, an attorney with Frier Levitt LLC, noted during a conference session on legal conundrums in specialty pharmacy.

Mr. Dresser advised that no matter the issue—compliance, network admission, site-of-care policies or reimbursement—it’s important to start with the patient and their type of plan. “That will dictate what laws and rules apply and what your rights and obligations are,” he said. As an example, he pointed to the three types of specialty pharmacy networks:

1. Closed or exclusive. “These are the ones where the sponsors are not allowing anyone in except their own wholly owned specialty pharmacy,” Mr. Dresser said. “We typically see these arrangements in the employer-sponsored commercial market. Large plan sponsors with thousands or hundreds of thousands of employees, like Pepsi-Cola, typically self-insure rather than spend an extra 10% to 15% on premiums on behalf of their employees, but they will still contract with an insurance company to administer their claims and PBMs to administer their pharmacy benefits. In this context, state laws don’t really apply and federal rules like those involving Medicare or Medicaid don’t really apply.” Plans like these, he noted, are subject only to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), which is silent on what pharmacies must be in a network.

2. “Open,” but with heightened ad-mission criteria. Such criteria include requirements for multiple forms of accreditation or licensure in all 50 states.

3. Truly open specialty pharmacy networks. “These are typically found in Medicare networks, where there is a robust federal Any Willing Provider law and a prohibition on payors from limiting who can be in the network,” Mr. Dresser said.

White and Brown Bagging Still a Concern

As for specific legal strategies to deploy, that depends on the practice challenge, he noted. One of the most problematic issues is the growing trend among PBMs to move claims processing from the medication side to the pharmacy side, requiring more white and brown bagging—a hot topic throughout the conference. The practice has had a major effect on hospital infusion, Mr. Dresser said. “About this time last year, several large payors took virtually identical steps to require that in-office infused medications be filled at their wholly owned specialty pharmacies, and placing limitations, or removing altogether, providers’ ability to source and seek reimbursement for medications administered in their facilities.”

There are laws being proposed in some states that would make mandatory white bagging illegal, but what can hospital and health-system specialty pharmacies do in the meantime?

“Depending on the type of plan involved, you might be able to deploy Any Willing Provider” legislation, Mr. Dresser said. “All 50 states and the District of Columbia, through Medicare Part D, are subject to the federal Any Willing Provider law, meaning that any willing pharmacy able to participate in a network’s terms and conditions has to be allowed in. The law is fairly robust, and its guidance requires that those terms and conditions have to be reasonable and relevant. It has been used successfully to protect not only network access, but fair and appropriate reimbursement for specialty pharmacies to participate in Medicare Part D programs.”

There also are some state-based Any Willing Provider laws as well as state laws banning mandatory mail-order pharmacy. “About 33 states have some level of this kind of protection,” Mr. Dresser said. “I would encourage anyone facing any kind of exclusion to figure out what type of network the patients you are not being able to fill for are in, and then see if you can use some of these legal tools to your advantage.”

Audits, Other Challenges

Mr. Dresser stressed that white bagging, although a big challenge, isn’t the only concern that HssPs have to address with legal tools, citing the following:

Fair pharmacy audit laws. “These laws apply at the state level, typically in the context of commercial insurance and not necessarily ERISA or Medicare,” Mr. Dresser said. “They provide time limits on PBM audits, as well as audit appeal procedures. They often limit the number of prescriptions that can be looked at in a given audit and, helpfully, prohibit recoupment for clerical errors or things that can be ‘cured.’”

Prompt payment laws. “These include look-back periods limiting PBM audits,” Mr. Dresser explained. “Florida, for example, says you can’t go back more than 30 months in terms of a repayment demand. They also prohibit PBMs from unilaterally offsetting claims to recoup on audits, saying, ‘You owe us $100,000, and we’re going to recoup it immediately. You can appeal but we’re going to start now.’ If you’re facing an audit and potential recoupment, this is a good tool to have in your arsenal.”

Mr. Dresser also spotlighted recent actions by PBMs in the 340B space. “They are trying to retain the spread between the costs of the 340B drug and the PBM reimbursement,” he said. “They send out notices to pharmacies requiring them to submit 340B claims with a submission clarification code to signal to the PBM that it is a 340B claim.”

This typically involves the use of a Submission Clarification Code of “20” in the NCPDP Field 420-DK. If a claim is 340B, the PBM then reimburses the pharmacy at a lower rate—for example, average wholesale price (AWP) – 30%, compared with a rate of AWP – 15% for non-340B claims.

“Essentially, PBMs are looking to usurp that savings for themselves,” Mr. Dresser said. “This is not necessarily limited to Medicaid programs managed by PBM; it could include commercial plans and often does. They are also using third-party administrators to get access to this information. Some PBMs own their own third-party administrators, so they might have the ability to make the determination, even if the pharmacy didn’t submit the clarification code at the point of sale.”

Mr. Dresser noted that there has been some success in pushing back against these efforts. “The tides have turned a bit in state legislation,” he said. “Some states, including most recently Ohio, have passed laws prohibiting PBMs from differentiating 340B and non-340B pricing. So, if you are facing mandates from a PBM that you use the clarification code, or otherwise encountering 340B-specific pricing, I encourage you to speak to counsel who can guide you on some of the recent tools that are available.”

Speeding Access To Medications

As noted, timely access to specialty medications was a key concern cited by respondents to the ASHP practice survey. At Mass General Brigham, in Boston, the solution to this challenge was to employ integrated specialty pharmacists in its health-system clinic to mitigate treatment delays.

In a retrospective chart review of 121 patients being prescribed specialty medications from an ambulatory autoimmune/allergy practice, the median time to dispense from prescription receipt was four days for the health-system specialty pharmacy and 13 days (P<0.001) for an outside specialty pharmacy. Using an integrated specialty pharmacy model versus a standard clinical workflow also yielded other benefits, including decreased time between PA requests and PA submission (one day vs. 12 days; P<0.001); and decreased time between the PA submission and recorded PA outcome (one day vs. 3.5 days; P=0.03).

“Timely medication access is a primary barrier in the treatment of patients with autoimmune disease,” said lead author Soha Elshaboury, PharmD, a pharmacist clinical coordinator for the health system. “This is mainly due to the cumbersome process around prior authorization and the resources it takes to coordinate this process.”

For the study, Dr. Elshaboury and her colleagues completed a retrospective chart review for patients receiving prescriptions for self-administered specialty medications between Feb. 26 and Dec. 24, 2020. These were largely for injectable medications such as dupilumab (Dupixent, Sanofi/Regeneron), benralizumab (Fasenra, AstraZeneca) and mepolizumab (Nucala, GSK).

Patients receiving a new prescription after Feb. 26 who required a PA to start therapy were categorized as the intervention group, for whom the specialty pharmacy staff processed the PA, reviewed therapy and consulted providers as needed for clarifications. Patients who received a refill after that date, in which they had a PA completed by clinic staff to start their therapy, were classified as standard of care.

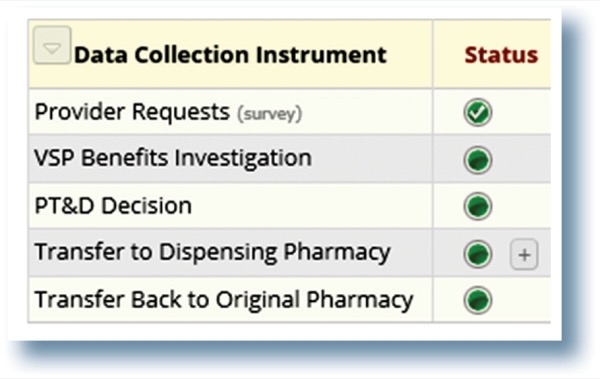

The investigators gathered data using electronic health records (EHRs), patient management software, adjudication software and records of phone calls to outside pharmacies.

The standard-of-care workflow started with a provider discussing therapy with a patient and asking them to complete the manufacturer’s hub form. The provider would then notify the medical assistants that therapy was to be initiated and would provide completed chart notes, the specialty medication prescription and completed hub form. The medical assistant would then request a benefits investigation via the hub by submitting the appropriate forms. After the benefits investigation, the clinic would submit the PA. If it was approved, they would send the prescription to the patient’s dispensing pharmacy or the provider would have to work on a PA.

In contrast, the specialty pharmacy intervention workflow focused on a real-time benefits investigation after the provider entered the prescription and submitted the PA as needed in real time. If a PA was approved, the prescription would be reviewed clinically and sent to an outside specialty pharmacy to dispense or to the integrated specialty pharmacy if they were a contracted pharmacy. If the PA was denied, a specialty pharmacy clinical pharmacist would work with the provider to either appeal the process or choose a different therapy.

Overall, time to medication access was reduced in the intervention group compared with the standard of care when an outside specialty pharmacy was used for dispensing, with the benefit compounded when the HssP was used for dispensing (seven vs. 37 days; P<0.001).

Dr. Elshaboury and her colleagues attributed the reduction in time to medication access to the following features of the intervention workflow:

- complete access to patients’ electronic medical records;

- use of software to manage PA requests;

- prescription capture at the time of prescribing;

- real-time benefits investigation;

- on-site PA submission;

- comprehensive clinical pharmacy review; and

- on-site medication dispensing.

The specialty pharmacy already had a relationship with the rheumatology, dermatology and inflammatory bowel disease clinics before the study. The autoimmune group was the last discipline being rolled out.

“We have gotten excellent feedback from our physicians,” Dr. Elshaboury said. “Everybody had a sense that we had drastically improved this process, but we really wanted to put a number on what that impact was, and we picked patient medication access, ultimately, as the best marker of that impact, and decreasing the time to medication access.”

Kudos for Brigham’s Effort To Embed Pharmacists

Embedding pharmacists directly in specialty clinics in this manner is what HssPs should do, commented Josephine Hurtado, BSPharm, the director of specialty pharmacy for Texas Children’s Hospital, in Houston. Doing so at her hospital has led to patients receiving new prescriptions for specialty medications in less than a day, as opposed to four days through outside specialty pharmacies, or about 9.5 days for new prescriptions needing a letter of necessity or PA.

These pharmacists are trained in specific diseases, and being housed in a clinic, patients get to know them, noted Ms. Hurtado.

“When the physician writes the prescription, we’re right there able to do any prior approvals, or ask any questions if there’s an error,” she said. “We can literally get up, go down the hall and have a conversation with a physician. Then we have access to all the labwork, so we can provide letters of medical necessity, or if there are any lab values or clinic notes that need to be reviewed, we can do so.

“I honestly believe that being part of a medical care team and being able to have that conversation where you know the physician by first name is very beneficial for us,” she added. “Otherwise, those outside pharmacies are calling and leaving a voice mail potentially and waiting for it to be returned.”

The sources reported no relevant financial disclosures.

This article is from the September 2021 print issue.