Audits of compounded sterile products (CSPs) by pharmacists at West Virginia University Hospitals, in Morgantown, saved more than $500,000 from unused medications in partially dispensed, discarded vials, system pharmacy leaders reported at the ASHP Midyear 2024 Clinical Meeting & Exhibition, in New Orleans.

The IV drug waste audits, conducted from January 2020 until June 2023, included CSPs and items returned to the pharmacy for disposal, specifically dispensed products that could not be re-dispensed per local policies and procedures, noted Marc Phillips, PharmD, CPHQ, the assistant director of pharmacy-supply chain and procurement at Ruby Memorial, which is part of West Virginia University (WVU) Health System. The audit excluded insulin syringes, narcotics and chemotherapy agents due to regulatory and safety reasons.

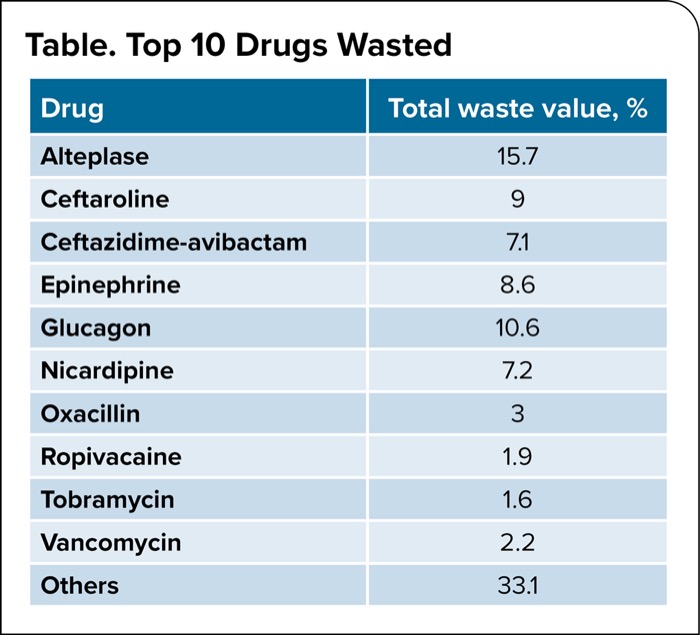

“We set up collection bins over our Stericycle units, both in our main pharmacy within our IV room, and then our OR satellite, where we also have a smaller compounding area,” Dr. Phillips said. “So instead of throwing away anything that wasted, we kept it to track the data. We annualized the results from that two-week period, and then quantified those losses. In our most recent study, the two-week loss was $12,886.77, for an estimated annual loss of $335,054.62, down from over $800,000 when we started focusing on this back in 2020.” Together, the top 10 wasted drugs accounted for 66.9% of IV waste, with an estimated annual loss of $224,098, he noted. (See Table)

| Table. Top 10 Drugs Wasted | |

| Drug | Total waste value, % |

|---|---|

| Alteplase | 15.7 |

| Ceftaroline | 9 |

| Ceftazidime-avibactam | 7.1 |

| Epinephrine | 8.6 |

| Glucagon | 10.6 |

| Nicardipine | 7.2 |

| Oxacillin | 3 |

| Ropivacaine | 1.9 |

| Tobramycin | 1.6 |

| Vancomycin | 2.2 |

| Others | 33.1 |

Common causes of IV waste included short-stability preparations, poor communication between clinical and sterile compounding staff, compounding errors, and improper batch sizes. Dr. Phillips and his team met with clinical pharmacists, IV room staff, pharmacy administration and supply chain officials to implement specific interventions, including changes of clinical processes, modification of batch levels, sourcing premix options and extension of beyond-use dates.

“One of the biggest sources of loss we identified was alteplase for chest tube installation,” Dr. Phillips said. “After we talked with the entire team, we understood the problem, which is why using our results to start a conversation was a true catalyst.”

During ICU rounds, he explained, an ICU team member would order alteplase and the care team then would continue on rounds. Next, a compounding pharmacy team member would make the preparation and send it up. “However, that team member, who by policy on the unit is the only one allowed to instill it, was still doing rounds,” Dr. Phillips said. “So by the time they were ready, the product that was sent up within 20 minutes was now beyond its use.” In such a scenario, “we were forced to throw it away and remake it to send up in real time.”

Their solution was to work with ordering providers “to time it for later in the rounds when they know they will have time,” Dr. Phillips said. “A simple conversation between pharmacy and our ICU teams saved a significant amount of money.”

Through those and other interventions, IV waste was reduced by 61% between June 2020 and June 2023, he reported, representing a total savings of more than $500,000 during that three-year period.

‘A Critical Issue’

These findings “highlight that IV waste reduction is a critical issue requiring more attention,” said Alex C. Lin, PhD, a professor of pharmacy at the James L. Winkle College of Pharmacy of the University of Cincinnati, in a separate interview with Pharmacy Practice News. Dr. Lin noted that IV workflow management systems (IVWMS) represent another strategy for significantly reducing IV waste. In a retrospective analysis of the implementation of IVWMS at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, he and his colleagues found that the adoption of the system significantly reduced the amount of wasted and missing IV doses by 14,176 and 2,268 doses, respectively (P<0.001), with overall cost savings of $144,019 over three months (Int J Med Inform 2018;115:73-79).

“Using the IVWMS facilitates the implementation and execution of optimal batch frequency and intervals, as well as a high level of process reliability,” Dr. Lin said. “We were able to reduce almost 80% of IV waste.”

More Savings Found

Dr. Phillips’ group at WVU has also been looking for additional sources of IV waste savings. For example, in March, they converted from compounding a 10-mL epinephrine low-dose syringe to a 5-mL syringe, resulting in a 50% decrease in waste, with no changes to product usage or restriction criteria. They also plan to reevaluate their batching values for oxacillin 2 g in IV piggyback.

“But we have now hit most of the low-hanging fruit, so a lot of what is still happening can only improve as we improve communications—around discharge, for example,” he said. “If a prescriber is going to switch this product from IV to PO [oral] in anticipation of discharge, how can we work with them to avoid batching unneeded doses?”

The sources reported no relevant financial disclosures.

This article is from the April 2025 print issue.